Donna Anderson Gross – WASPs

Donna Anderson Gross Audio

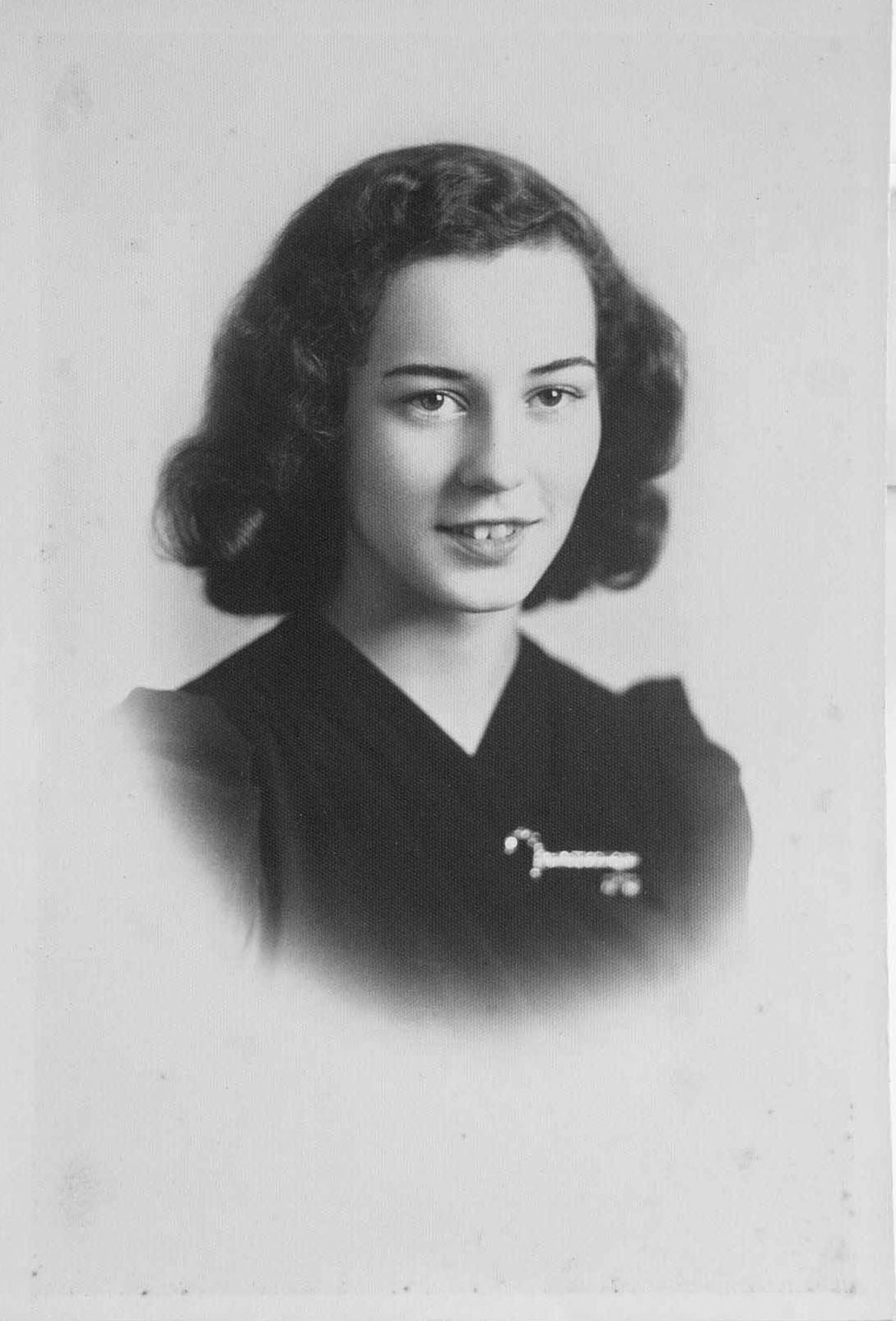

As DeWitt County’s youngest aviatrix, Donna Mae Anderson ascended the limits of aviation for female pilots before her dream of becoming a commercial flyer was cut short by the winds of politics and gender discrimination.

Anderson’s passion for flying was fueled by the planes she watched on air strips within view of her home near Midland City, a town that amounted to a cluster of houses on the border between DeWitt and Logan counties.

“Mom was kind of a tomboy. We always knew she flew a plane, and she was an expert with a rifle. She once won a dog in a hunting competition against men,” recalled Diana Gross Battiste, the pilot’s daughter.

By 14, she was learning to fly a plane and by 17, she was garnering media attention as “DeWitt County’s first and only aviatrix” after she earned her student pilot license. Part-ownership in a plane owned by the Clinton Flying Club and a job as assistant manager at the Decatur Airport were among her accomplishments as a teen. She also was a member of the Civil Air Patrol.

But Anderson, later known as Donna Anderson Gross after she married, considered the airport post a steppingstone to her career as a commercial pilot. The unavailability of flying schools and small airports that were training men for the armed forces seemed to close the door for military flight training.

Undaunted, Anderson Gross anxiously awaited her 18th birthday – the age she could legally apply for a position with the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASP), a group initially used to ferry Army Air Force trainers to their destinations and light aircraft from the factories. The female pilots later delivered fighters and bombers as well.

Anderson Gross also passed the time working at a factory in Illiopolis near Decatur that manufactured small artillery shells.

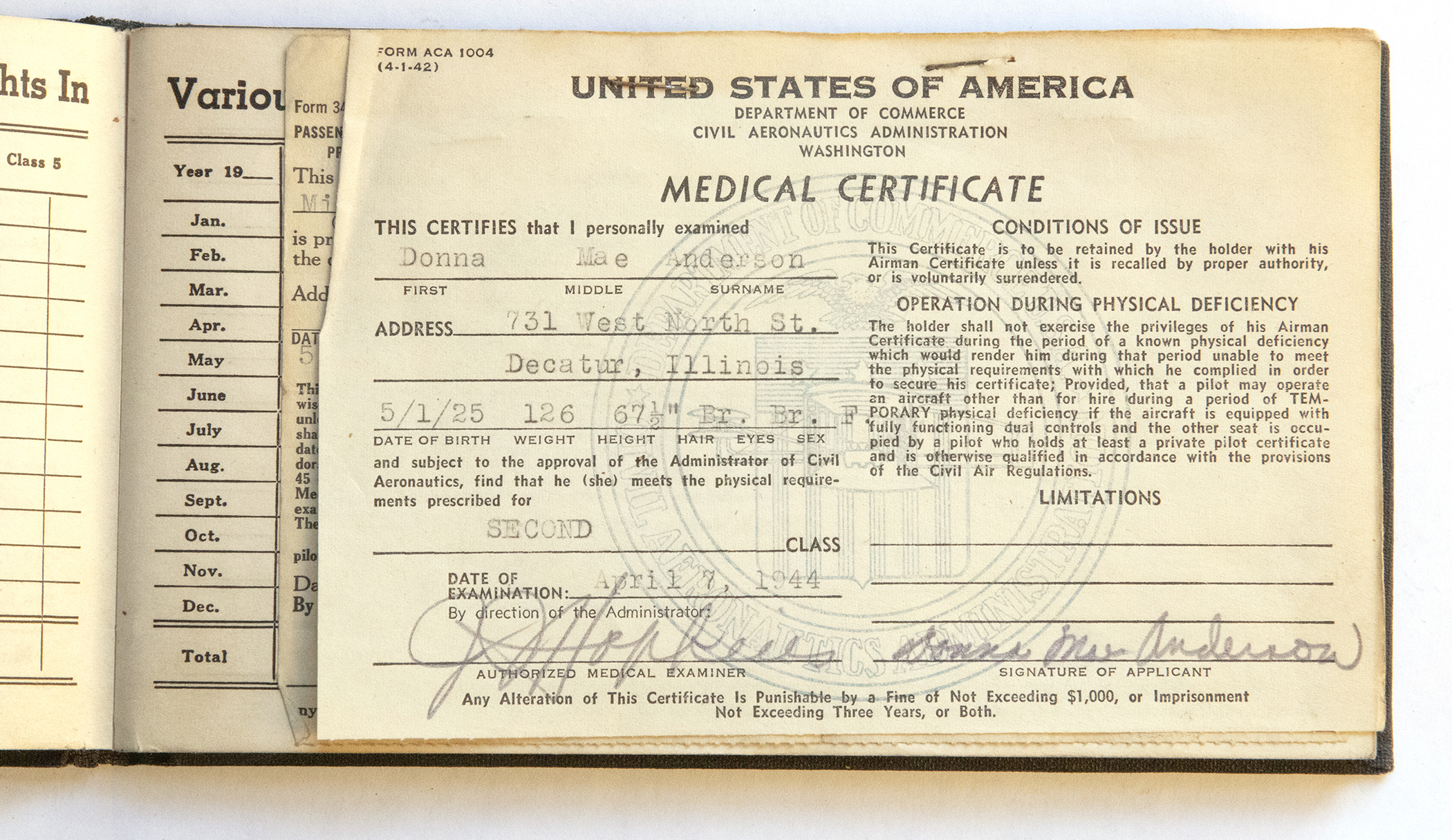

On June 6, 1944, while living in Decatur, Anderson Gross received her acceptance letter for the Women’s Flying Training program in Sweetwater, Texas. She was instructed to bring her pilot’s logbook and certification for admission. The training at Avenger Field was 30 weeks and 210 hours of flying.

The salary for the Civil Service position was $150 per month during training and $250 monthly as a utility pilot, if she passed the course. Transportation costs to the air base – and back home if a trainee washed out—were paid by the pilot. Expenses for “subsistence and maintenance during training,” were paid by students. The cost of room and board was estimated at $1.65 per day.

The handbook for trainees cautioned that “you are entering upon a phase of your life which will be so changed and so different from that to which you have been accustomed, that it will seem to be a new existence altogether.”

Famed female pilot Jacqueline Cochran was hired to lead the initiative to use the talents of female flyers as part of the war effort. Hundreds of women enrolled in the program the first two years.

Donna Mae Anderson’s dream of flying for the military was disrupted after she and hundreds of other young female pilots found themselves in the crosshairs of a political debate over whether women should serve in the military. A proposal to militarize the WASPs was met with strong opposition from some male aviators and members of Congress, along with influential members of the media.

In a series of emails she penned to her children shortly before her death in 2001, the disappointment remained palpable.

“I finally reached the old age of 18 and was called to report to the WASPs. Had a big farewell party at the plant and went home to pack my bags for Waco, TX. I was to leave Saturday at 6:00 p.m. My Dad came home with the telegram that told me my class was canceled and there would be no further classes. Seems Ms. Cochran wanted us admitted to the armed services and the Senate wouldn’t allow it.”

The young aviatrix knew the breadth of her abilities and the loss the military suffered by denying admittance to her and other experienced flyers.

“I had to go to Chanute Air Field for written and physical training. The exam was the same as they gave commissioned officers and I passed. So had I been a man, I would have at least been a lieutenant,” she wrote.

The contributions of female pilots were well documented during the two years they were allowed to assist the military.

“They fly the equivalent of more than seven times around the earth every day and pilot planes of many types and capabilities, from trainers up through the Thunderbolt, Mustang, Marauder and Fortress,” the New York Times noted in a March 1944 article on the issue.

Advocates for women pilots rallied support and attempted to push through legislation that would allow the program to remain open. Anderson Gross and others whose careers were derailed by politicians received letters from women in Washington D.C. urging them to fight on. Letters to lawmakers and newspapers followed.

“It became a matter of men’s rights vs. women’s rights and the male pilots being effectively organized were able to prevail with Congress at your direct expense,” wrote two advocates in a letter to the DeWitt County student.

The WASP program received more 25,000 applications, with 1,830 accepted. Graduates numbered 1,074 and 900 remained when the program ended.

After the program was disbanded, many WASPs who wanted to continue to fly were rejected by commercial airlines fearing a negative backlash of public sentiment. In 1949, the U.S. Air Force offered commissions to former WASPs but it did not include the ability to fly for the military.

Women first entered Air Force pilot training in 1976 and fighter pilot training in 1993. Today, the Air Force has 960 female pilots and 417 women serve as navigators.

After several weeks of unsuccessful lobbying of lawmakers, Anderson Gross went back to work at the Garfield Division of Houdaille-Hershey in Decatur where she served as a secretary to the plant manager. She later moved with the company to Detroit where she met her husband Don Gross and they started a family, a daughter Diana and son Don.

The family returned to Kenney in 1966 to live on the Anderson homestead. Anderson Gross worked as a secretary for the Clinton law firm of Herrick, Rudasill and Moss.

Her skill and knowledge of aviation never waned.

After watching landings by her neighbor John Warner at Hooterville Airport near Hallsville, she offered him some advice.

“I stopped and watched your landings. If you’ll slow your approach and pitch the nose up a little more when you touch down, your landings are going to be a lot of better,” Warner recalled her telling him.

It was clear to Warner that he was getting good advice. “I realized, ‘you know what you’re talking about.”

In conversation with her children, Anderson Gross shared the single contribution she felt she had made during the war effort. It came during her time at the Garfield plant.

“Our secret was revealed when the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Japan, and the war was over. We made a small little part of the bomb but received the Army-Navy E Award and a big celebration.”

Recent Comments