Ernest Thorp – B-17 Bomber Pilot

Every generation has its true heroes – those who raised their hands without hesitation and said “I’ll go” in response to a nation in need, leaving loved ones behind as they faced unknown dangers far from home.

Before they became heroes, soldiers lived in neighborhoods and, in the case of Ernest Thorp, on farms in the heartland. Thorp’s story as an Army Air Force pilot begins with his childhood admiration for aviator Charles Lindbergh, a man he considered his hero after the pilot’s famous 1927 flight across the Atlantic.

The decision by Thorp’s close friend Gordon Hall, another resident of the small town of Wapella, to become a military pilot, also influenced Thorp. Before he was killed in a crash while flying a captured German aircraft in Italy, Hall flew B-25’s, the plane Thorp hoped to fly when he joined the military.

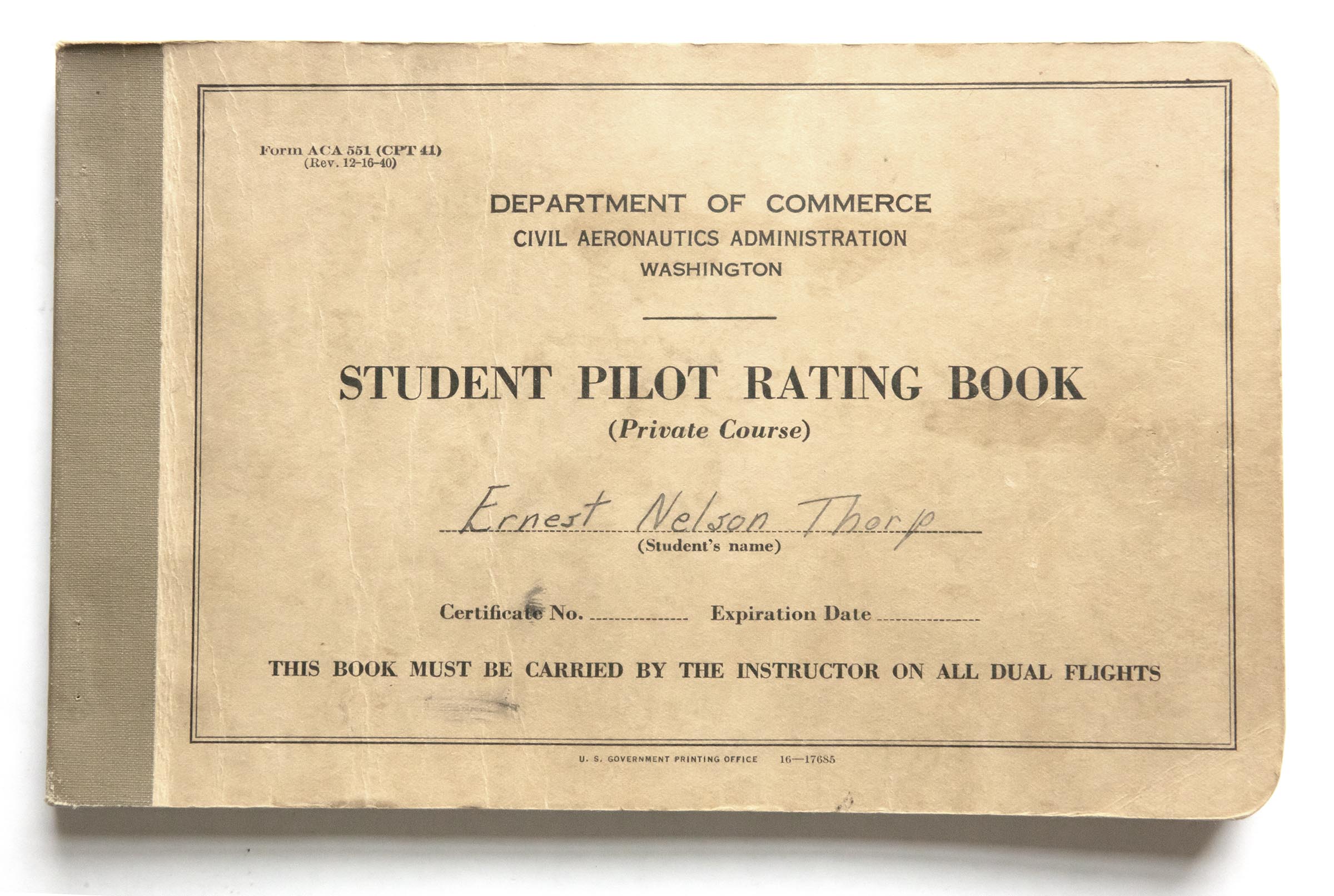

In 1939, Thorp started college at Illinois State University (formerly Illinois State College) and transferred to the University of Illinois two years later where he learned to fly. He enlisted in the Army Air Force in 1942 while still a student and completed the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program.

In March 1943, mid-way through his senior year, Thorp was given full credit to graduate by the university and left for Basic Training in Texas. His family would later receive his diploma while he was a prisoner of war.

Thorp’s determination to be a pilot diminished any fears of the dangers encountered by wartime aviators.

“That’s one of the things that’s kind of strange in a sense, but you were always going to be the mother’s son that never got hit. In other words, they would get the other guys – not you…. I didn’t think it could happen to me or would happen to me,” Thorp told an interviewer in a lengthy 2009 conversation for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield.

Much of the detailed account of Thorp’s military service comes from a diary he kept throughout his 40 months as a pilot, including the nine months he spent as a prisoner of war. “My Stretch in the Service” was widely shared by Thorp before his death in 2017 at the age of 95.

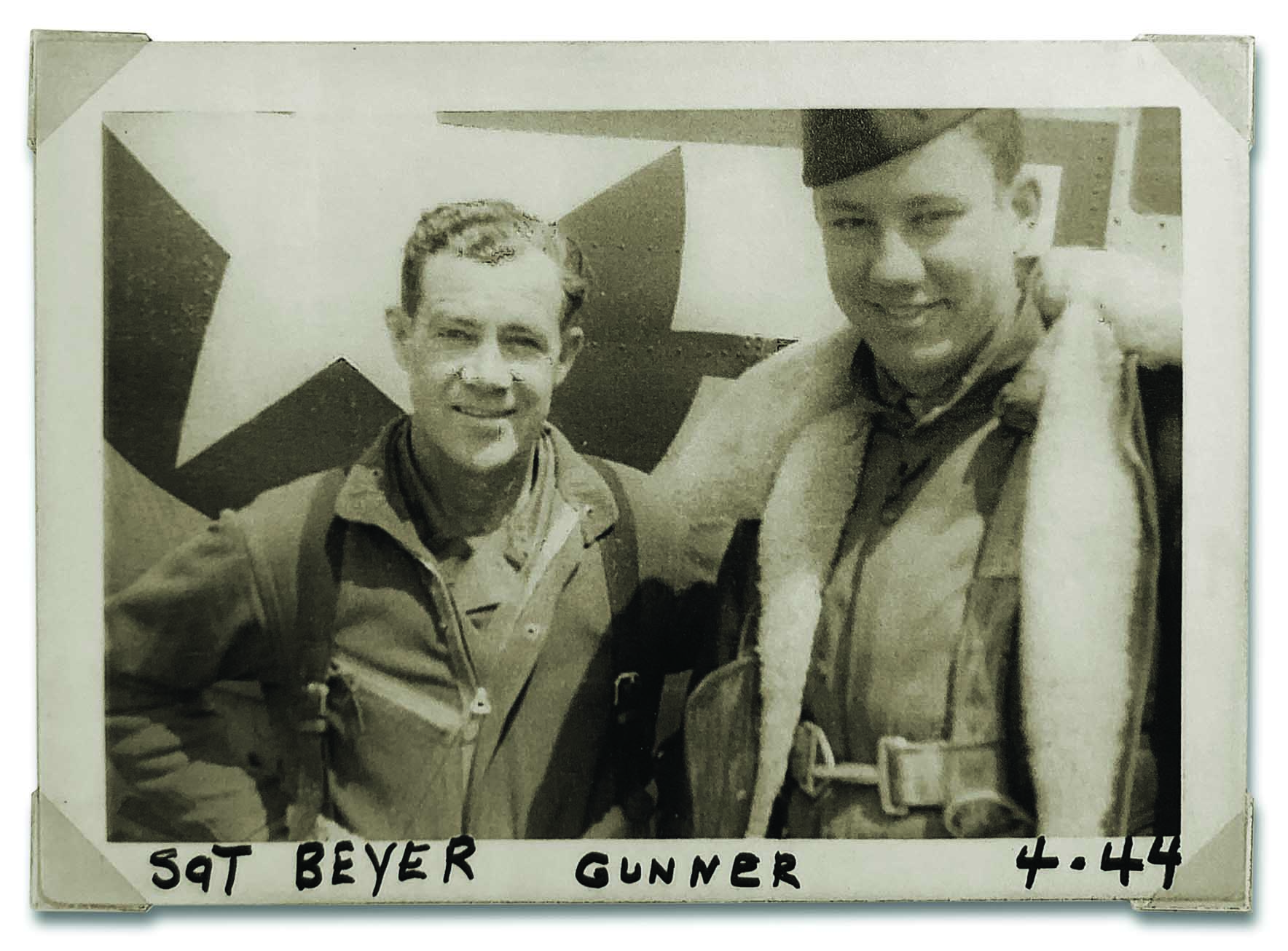

Following flight training in Oklahoma, Thorp was assigned to a B-17 crew as a co-pilot. His crew took off in May 1944 from a training facility in Sioux City, IA for Deopham Green, England as part of the 729th Squadron, 452nd Bomb Group.

In a diary entry written after a practice formation mission, Thorp recalled seeing a crash nearby:

“Watched a British Lancaster circle the field, stall out and crash about a mile from where I was at. Exploded and burned. I don’t know how many escaped. Combat is getting closer every hour. Seeing these planes land with their wounded and battle-damaged gave me a funny feeling deep inside that you just can’t laugh off all that well.”

During his missions over both occupied France and Germany, Thorp saw many planes go down along with their pilots and crews. He reflected on the consequences of the war in his journal.

“Boy. On the bomb run, you get a funny feeling all those bomb bay doors open, knowing soon death and destruction will fall from the insides. It’s just like watching a long fly ball hit way out, and you hold your breath until you see the results: a hit, an error, foul-out, et cetera,” Thorp wrote after his 15th mission.

Thorp opened his diary on Aug. 4, 1944, with a note that “this day began as a snafu right from the beginning.” Upset that a paperwork error kept him from a scheduled trip to London on leave, Thorp was assigned a new, somewhat anxious crew on a plane that would take off in heavy fog.

Things would only get worse on his 18th mission.

After the plane was hit multiple times by flak, Thorp took over the controls. With no hope of bringing the plane down safely and a noticeable fire over the left wing, Thorp made the decision to bail out over the North Sea.

After 45 minutes of intense prayers in the cold water, a mast appeared, one of the fishing boats that had spotted the four-member crew.

“I thought it was going to pass me up, but it eventually turned and headed my way. I shouted and tried to wave, and lo, the mast changed course and headed for me. It was a fishing boat and never a more welcome sight for a guy in my situation, though I knew the occupants would be Germans,” Thorp wrote in his diary.

The fishermen picked up Thorp, along with his pilot, navigator, and an engineer. They were given a shot of rum – a first for the non-drinking farmer –and wrapped in blankets.

“We were now prisoners of war – no more missions for us.”

Thorp spent the next nine months in a series of POW camps, starting with Dulag Luft and later Stalag Luft III in Sagan, shortly after the daring “Great Escape” in which 77 Allied prisoners managed to tunnel their way of out of captivity. (Most were recaptured within days.)

In late January 1945, with Soviets approaching, Thorp and other prisoners were forced to march to Stalag Luft VII-A during the coldest German winter in living history. The POWs lacked food, clothing, and medical care. At one point, the men were crammed into a boxcar –sixty POWs packed like sardines—for three days and three nights.

Thorp narrowly escaped being shot during the stay at Stalag VII A “because I was trying to slice a piece off a board to burn, and here comes a general with a tommy gun and I ducked around a corner. He didn’t chase me, fortunately, but I could have been shot for doing that because I was destroying Germany’s property,” Thorp recalled in the museum’s interview.

On April 29, 1945, a calm, peaceful Sunday morning, the POWs were getting ready for chapel outside the barracks when an American P-51 did a barrel roll over the barracks, setting off cheers. The sound of gunfire told them American troops had to be close.

When the soldiers saw the American flag go up over the town of Moosburg, they knew the news of their liberation was real.

“That’s when you see 100,000 men cry, cheer, pray – bedlam. Then the tanks come in, knocked down the gate and come parading down the corridor, covered with humanity. Everybody crawled on these tanks, POWs, just for the ride. And then we knew we were free men,” Thorp recalled.

After twelve days of medical care and rest, Thorp was on his way across the Atlantic, headed home after a harrowing time abroad. A steak dinner at Fort Dix in New Jersey came with a train ticket to Chicago, the final stretch of Thorp’s journey back to the farm.

Thorp planned to buy a new uniform and surprise his fiancée, Mary Ellen Harris by showing up unannounced in Wapella. When he couldn’t find the uniform, he boarded the Green Diamond for the one-way train trip to central Illinois.

As Thorp left his seat for the platform, he saw that the surprise was on him. Watching patiently as the passengers left the train, Mary Ellen searched for her beloved pilot. Knowing it would take several days for him to arrive once he made it back to the U.S., she went to the station and met every train, hoping he would be on board.

“As she saw me, I gave a weak salute with a drum in my throat…Home at last after 18 months’ absence. Many a time it seemed a dream unlikely to come through or true. Home is my home,” Thorp wrote in his wartime journal.

During his extended leave, Thorp and Mary Ellen married. She accompanied him to the Army Air Force Redistribution Center in Florida. It was time to decide on whether he would remain in the military.

The growing demands of Thorp Seed Company, operated by Thorp’s father and brother, were behind Thorp’s decision to leave the military. He continued his service in the Air Force Reserves and retired as a captain.

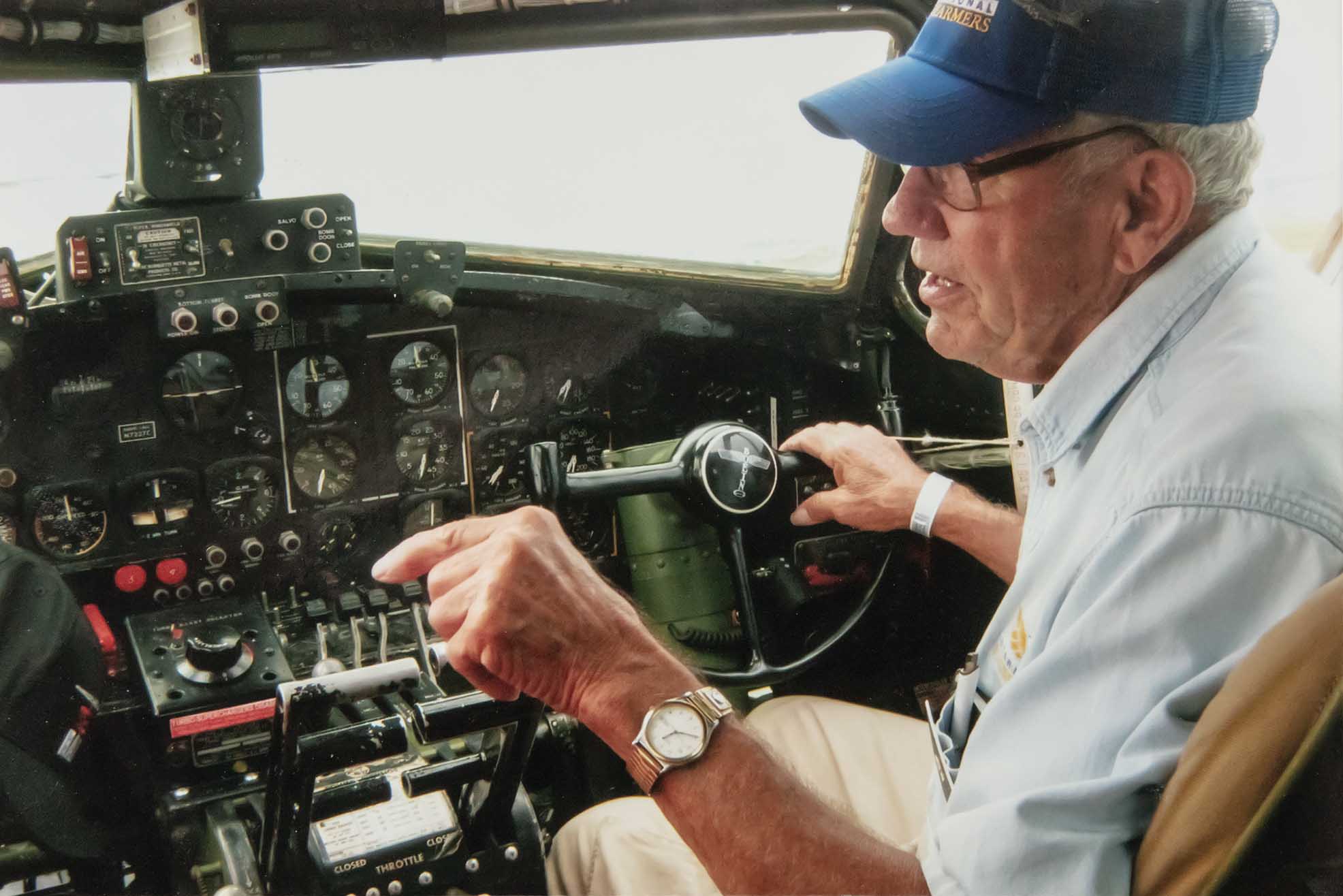

Back in DeWitt County, Thorp never gave up his love of flying. Thorp Seed Company maintained the county’s largest landing strip, with planes that played a key role in the agricultural business. Three of Thorp’s five children learned to fly, and the family was active in the Flying Farmers for many years.

Thorp was proud of his military service and seven decades as an aviator with more than 7,000 hours of flight time. He spoke to school and veterans’ groups about his experiences.

In his late 80’s, Thorp noted that he was still legally qualified to fly his Cessna 150 and Cessna 182 for another year.

“Who knows – at my age, who knows? So, I’m doing what I’ve always dreamed I wanted to do.”

Recent Comments