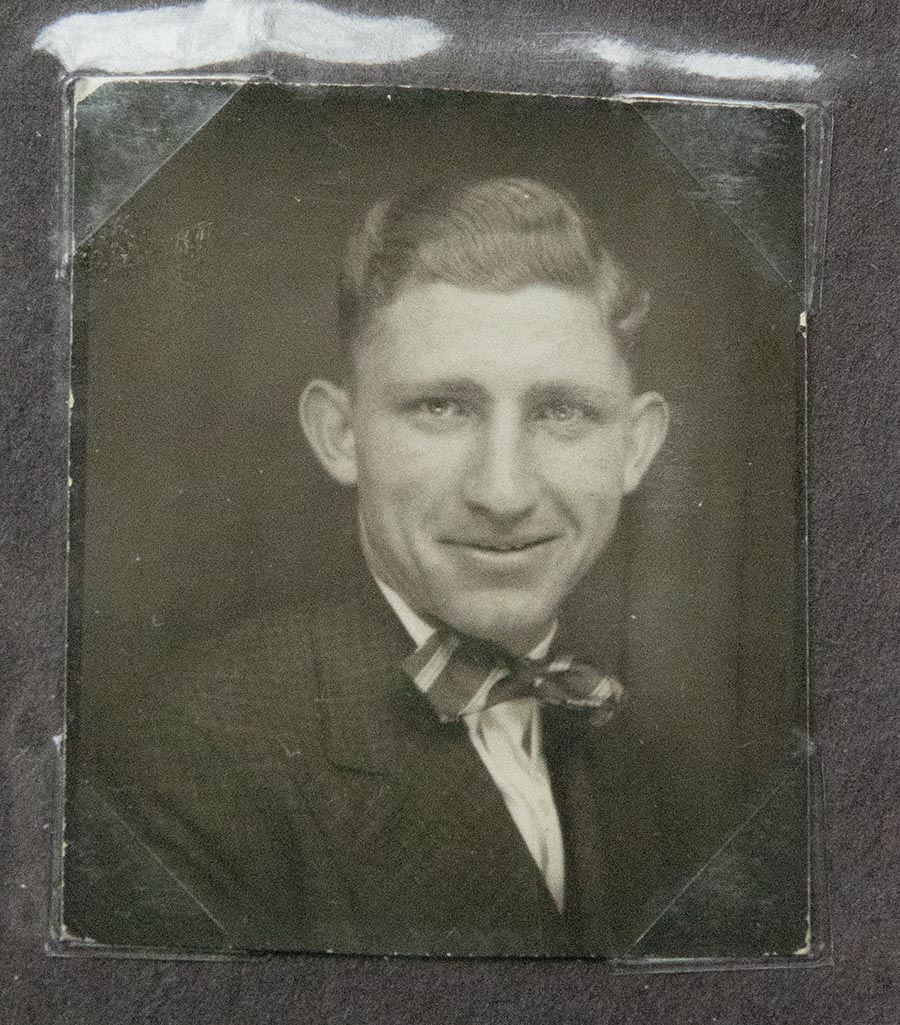

Gordon Hall – Army Air Corps Pilot

The people who knew Gordon E. Hall the best were not surprised that he soared up the ranks of the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Like many young men, Hall was eager to serve his country as soon as he collected his diploma from Wapella High School in May 1935. But the 17-year-old was a few months shy of being old enough to join the ranks. Hall enrolled at the University of Illinois, studying commerce and business administration, while working to complete flight training at Chanute Air Base in nearby Rantoul.

Hall’s friends waited anxiously for their 18th birthdays and the potential start of their commitment to the military.

Among the hometown students influenced by Hall’s decision to become a pilot was Ernest Thorp, who watched in amazement as Hall swooped low over the high school and the Hall’s home, a sign to the pilot’s parents that he was ready for a ride home from Chanute.

Hall was awarded his wings, along with a second lieutenant’s commission, following advanced training in November 1940 at Gulf Coast Air Corps Training Center, at Kelly Field, in Texas.

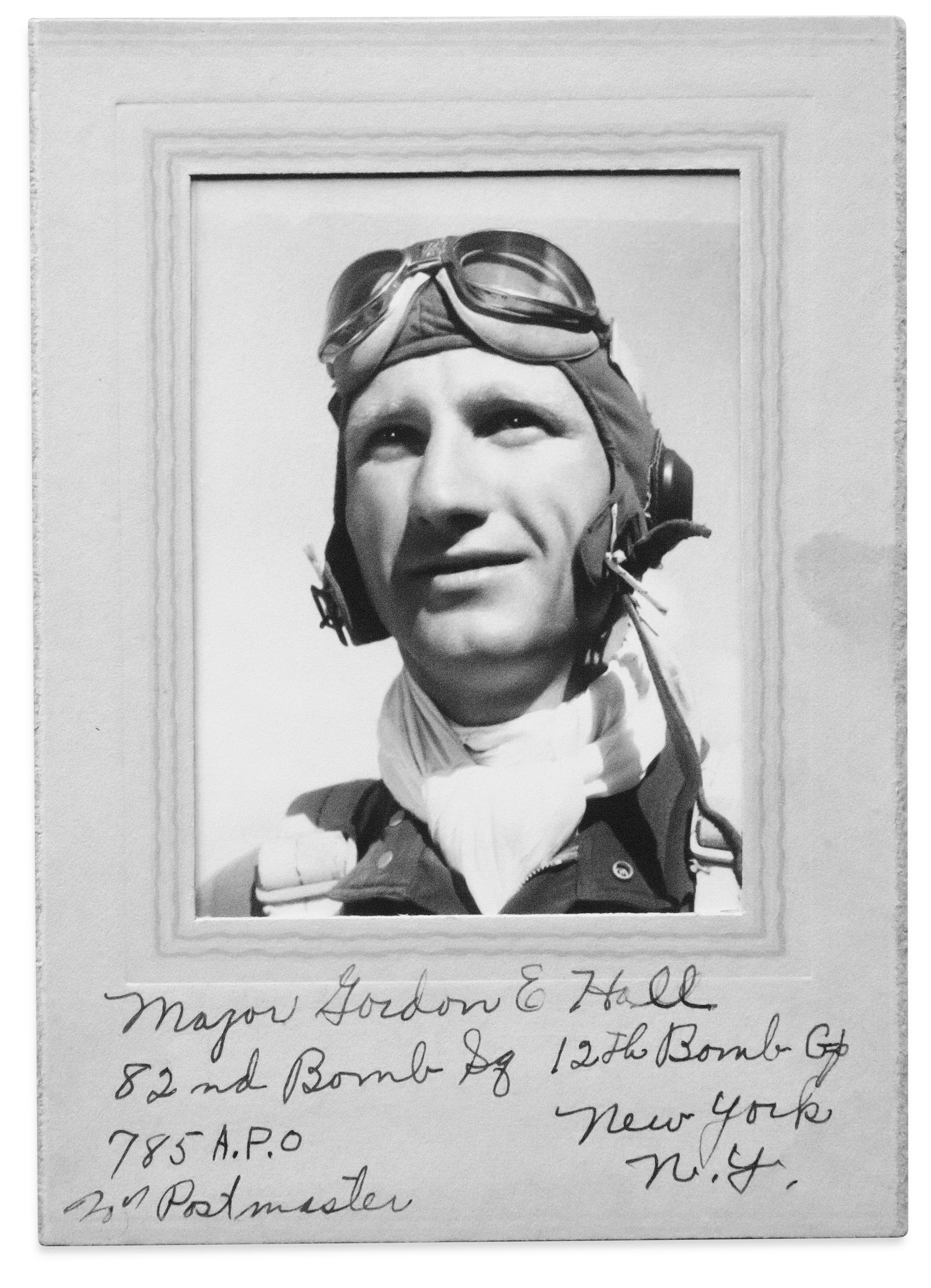

In July 1942, Hall and the other members of the 12th Bombardment Group left Fort Dix, New Jersey for overseas duty. The B-25 bomb group, known as “The Earthquakers,” were assigned missions in Northern Africa, Egypt and the Mediterranean.

Tech. Sgt. Robert E. Wilson chronicled the group’s experiences in “The Earthquakers: Overseas History of the 12th Bomb Group,” Written in frank “call a spade a spade” terms, Wilson’s book is a firsthand account into what the group encountered.

Near misses were recorded.

The first came over Egypt in October 1942 when a German 88 mm shell hit his plane in the squadron. The shell passed through the wing structure, leaving a gaping 14-inch hole but the crew intact. About a year later, Hall narrowly escaped death while flying as co-pilot with an Italian pilot in an SM -79 medium bomber. After receiving a few instructions, Hall took over as pilot on a second flight.

“Evidently there was some miscommunication as to who worked what, because the take-off ended in a broken landing gear and a smash-up,” Wilson wrote in his diary. Unable to break free of an Italian parachute, in the plane with one engine ablaze, Hall was rescued by the co-pilot.

Hall flew close to 50 missions, including the group’s first mission in Egypt in August 1943 against enemy airfields at Daba, Fuka and port facilities at Matruh. In a United Press story quoting the young operations officer from central Illinois, the raid was termed “a vicious dogfight.”

“One of the bombing squadrons in the all-American formation was led by Capt. Gordon E. Hall of Wapella, Ill. A tall blond, he claims to have the “best gunner in the outfit” – Tech. Sgt. William T. Cross of Terrell, Texas. “The gunner has the toughest job of them all,” Hall said. “He has to keep the pilot posted on what’s going on,” the reporter wrote.

The Aug. 17, 1943, edition of Stars and Stripes notes the 12th Bomb Group’s first anniversary of overseas battle. By the time the group moved to Sicily, Hall was 25 and one of the youngest men to serve as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army.

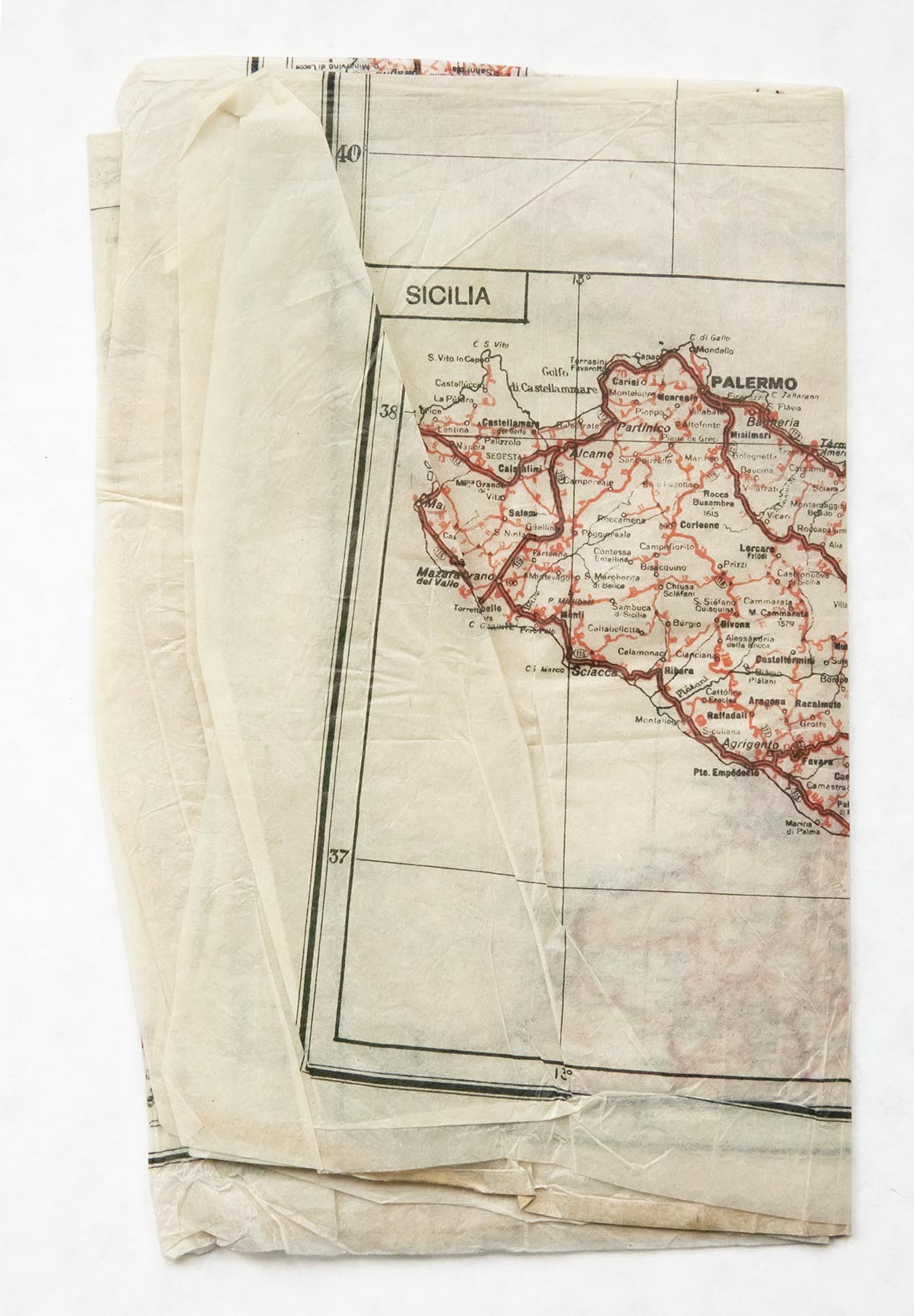

One of Gordon Hall’s tissue escape maps. Issued to pilots in case they are shot down over enemy territory.

`Hall received four citations in 1943, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Oak Leaf and several clusters and the Silver Star. The 12th Bomb Group was recognized with a Distinguished Unit Citation for its actions during the north African campaign.

Back home in Wapella, Hall’s parents John and Erma, and his three sisters, Eleanor, Geraldine and Gloria, stayed busy as they waited for their son and brother to return home. John Hall worked for a water well company and later served as a Clinton police officer.

Erma Hall’s new position at her brother’s service station garnered headlines in an area newspaper.

Hall’s “blue-eyed vivacious mother is doing her bit on the home front by taking a man’s place as Clinton’s first and only woman filling station attendant,” noted the July 1, 1943, Daily Pantagraph story.

“This kind of work keeps me busy and I don’t have time to think of things…. I’m sure proud of my boy,” Mrs. Hall told a reporter.

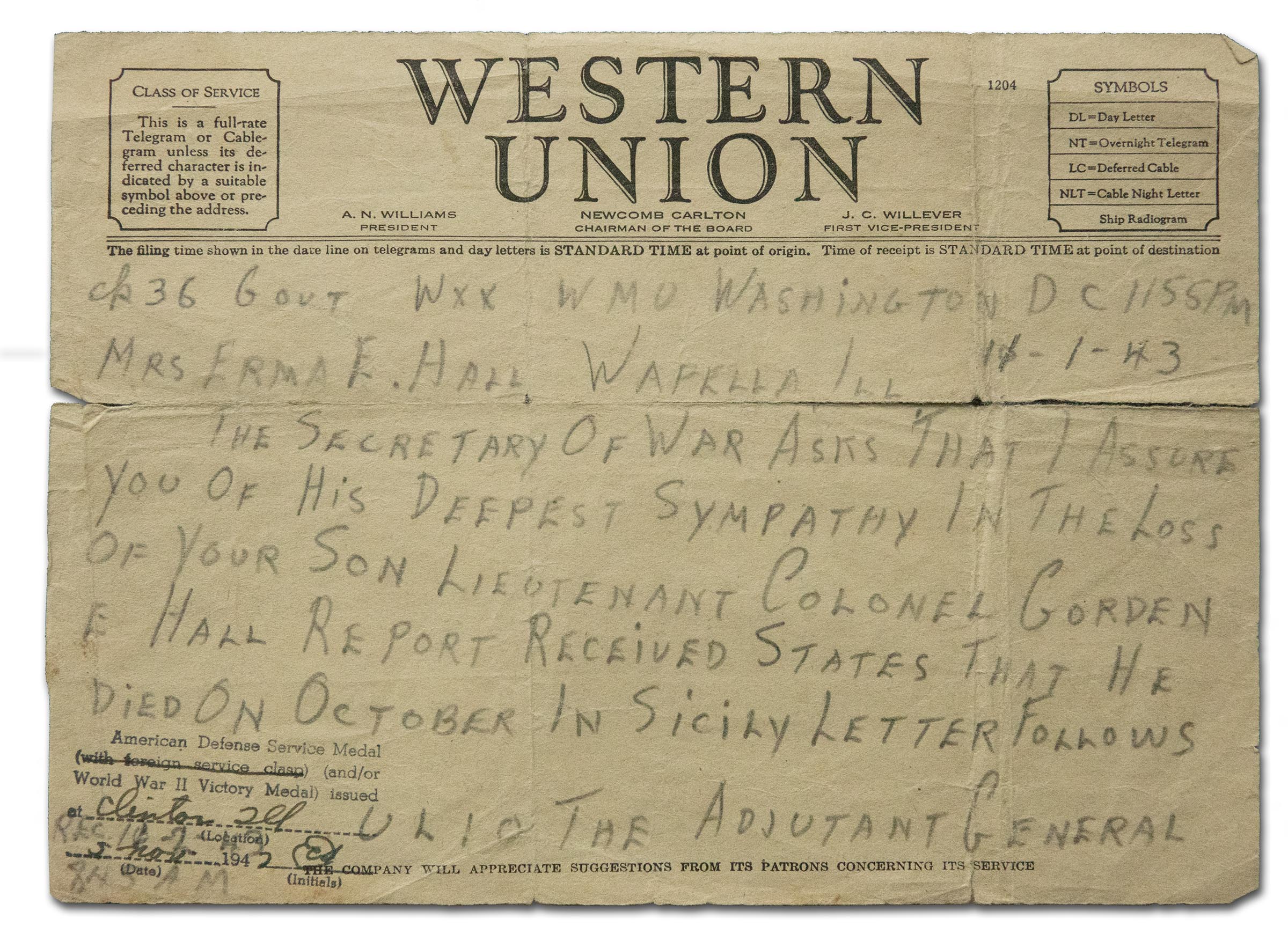

But the family’s worst fears were realized on October 1, 1943, when Lt. Col. Gordon E. Hall was killed in what was described by high-ranking officer as a “freak accident” in a twin engine German plane in Sicily.

Wilson watched as the tragedy unfolded and later wrote this account:

“On October 1st, the 12th Bombardment Group suffered their biggest loss to date overseas. Lt. Col. Gordon Hall, Operations Officer of the Group, had located a Me 210 and had it repaired. Impatient to go up in this plane, the Colonel decided on the 1st to take off just before dinner. At 1130 hours he taxied on the runway and opened the throttles. No one will ever know for sure what happened but one engine ran away, the plane veered to the left though it kept rolling and finally raised off the ground. About this time the plane left the ground, the nose cannon fired a couple of shots. Why this happened was a mystery. When I saw the Colonel, he was clear of the ground and just leaving the landing area. Immediately after he left the field plateau, he soared possibly a 100 feet high. He went into a vertical bank to the left and dived into the ground. The plane exploded and caught fire immediately. “For nearly an hour, the fire raged. Cannon shells and ammunition exploded every few seconds.”

Hall’s body had been somewhat protected from the fiery crash by tires that had fallen on top of him, Wilson writes. His watch and wallet were recovered.

Hall’s body was escorted to the base at Ponte Olivio the next day by a formation of three B-25 Mitchells.

“The death of Lt. Colonel Hall was certainly a shock to us. It had all happened so fast it was difficult for us to realize it,” Wilson recalled.

News of Hall’s death was delivered to his family in a handwritten telegram.

In a November 2, 1943, letter confirming the telegram message, Major General J.A. Ulio informed the parents that initial casualty reports indicate their “was killed in an airplane crash.” The Army official promised more details, when and if they became available.

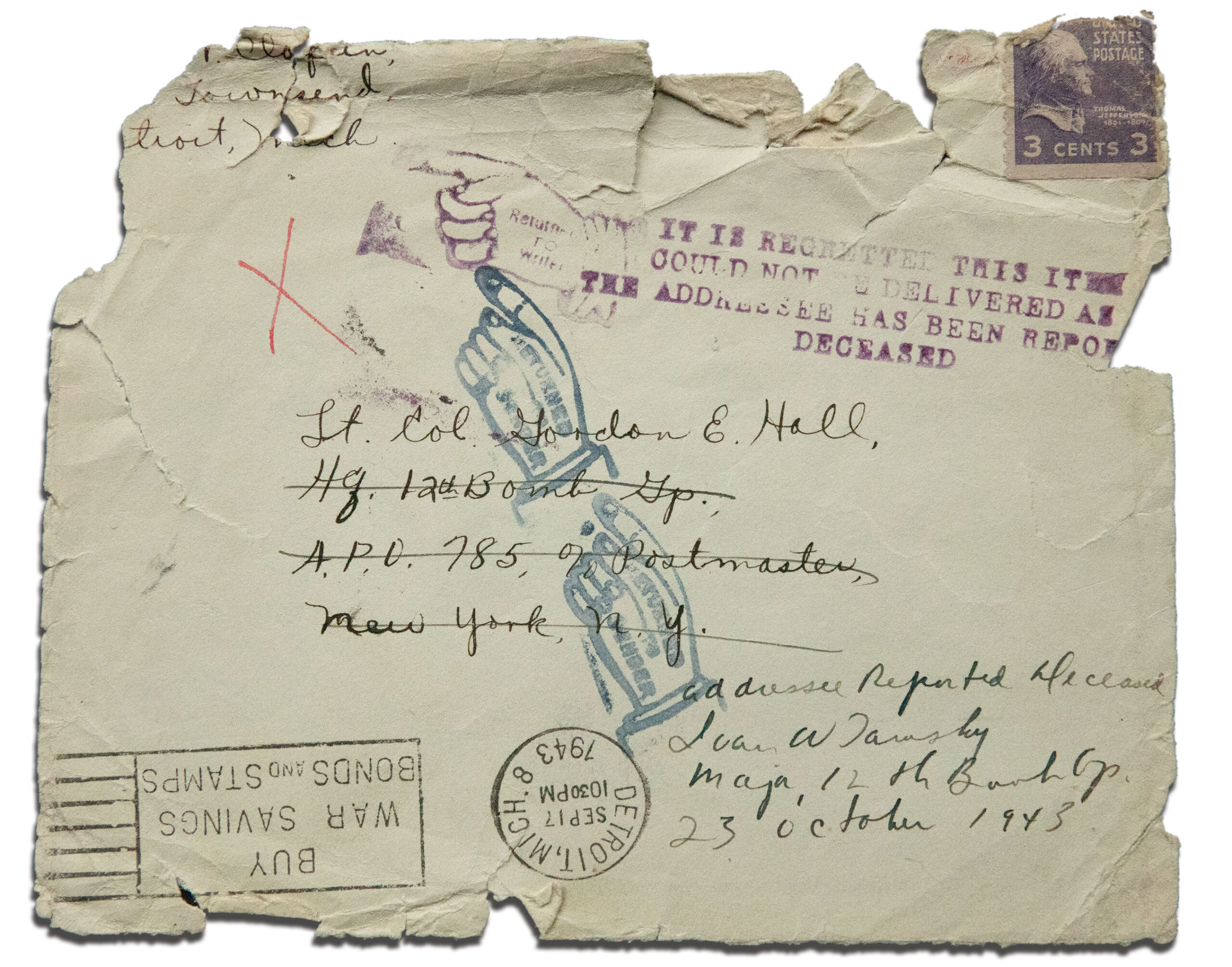

Tragically, this letter addressed to Gordon Hall arrived after he was deceased and was therefore return to its sender.

As the community and family prepared for Hall’s funeral at the Wapella Christian Church, the unanswered questions surrounding the crash added to everyone’s grief. Erma Hall continued to search for answers and 23 years after the loss of her son, Brig. Gen. William A. Wilcox provided insight into what had happened on the hillside in Sicily.

“For reasons that are unknown, Gordon’s aircraft lost power almost as soon as it became airborne – and at the same time, he was over the end of the runway,” the officer wrote in his letter to Hall’s mother. The crash, he was in, was unavoidable, but Hall’s one last act “of extreme presence of mind” kept others from becoming casualties.

“I must now explain that the major portion of our encampment was nestled against a hill, and the runway was on top of the hill. If Gordon had continued to glide, straight ahead from the end of the runway to his crash, he would have certainly plowed through many of the tents of the camp and killed many others with him.

“This he did not do. He kept his head and steered the plane sharply to the left and thus saved many who otherwise would have been victimized. He selected the isolated area and drove his plane to that spot for the crash,” wrote the Air Force general.

The operations officer “was a true flier, and I don’t think he could have wished for himself a more fitting end,” wrote Wilcox.

The general’s opinion that Hall deliberately steered the plane away from his comrades dampened a suspicion that the plane had been booby-trapped by Germans, a practice used by the enemy to harm and deter Allied troops from recovering downed aircraft.

“This he did not do. He kept his head and steered the plane sharply to the left and thus saved many who otherwise would have been victimized. He selected the isolated area and drove his plane to that spot for the crash,” wrote the Air Force general.

The operations officer “was a true flier, and I don’t think he could have wished for himself a more fitting end,” wrote Wilcox.

The general’s opinion that Hall deliberately steered the plane away from his comrades dampened a suspicion that the plane had been booby-trapped by Germans, a practice used by the enemy to harm and deter Allied troops from recovering downed aircraft.

Hall and a second solider killed overseas, Pvt. Richard Evey, of Clinton, were honored in 1945 when the Clinton Veterans of Foreign Wars post was named for the two fallen soldiers. Hall’s body was returned to Illinois where he was laid to rest in Woodlawn Cemetery in Clinton.

A postscript to Hall’s story was discovered in the January 1999 issue of Flying magazine. Hall’s longtime friend Ernest Thorp, another World War II veteran who was held as a prisoner of war, noticed Hall’s name in an interview with Army photographer Howard Levy.

Levy “got off one shot as the bomber went howling past towards its, and its pilot’s, explosive destruction moments later,” according to the photographer’s account.

Gordon Hall’s Navigation Briefcase

Diana Douglas, wife of Hall’s nephew Gordon Douglas, tracked down Levy in 2000 in hopes that final photo of Hall could be located. With Levy’s help, the family secured a photo of the pilot in the Me410 shortly before takeoff but the final image was never found.

Hall’s legacy is preserved in several large binders filled with flight records, photos, letters, and souvenirs kept for decades by his parents and sisters and organized by Diana Douglas.

In a final thought written by Diana Douglas as part of Hall’s biography, she recalls Ernest Thorp’s opinion that Hall had the makings of a general, adding “we’ll never know.”

The country lost “a pretty special person, even a hero,” Douglas wrote. The photos and other mementos lovingly saved by the pilot’s family for decades would have to tell his story.

“Until now, Colonel Hall and his activities have been pretty much taken for granted. It’s too bad that our family, as well as future generations, have to get “acquainted” with him through photos and articles. Fascinating—the adventures he lived and the stories he could have told.”

Recent Comments