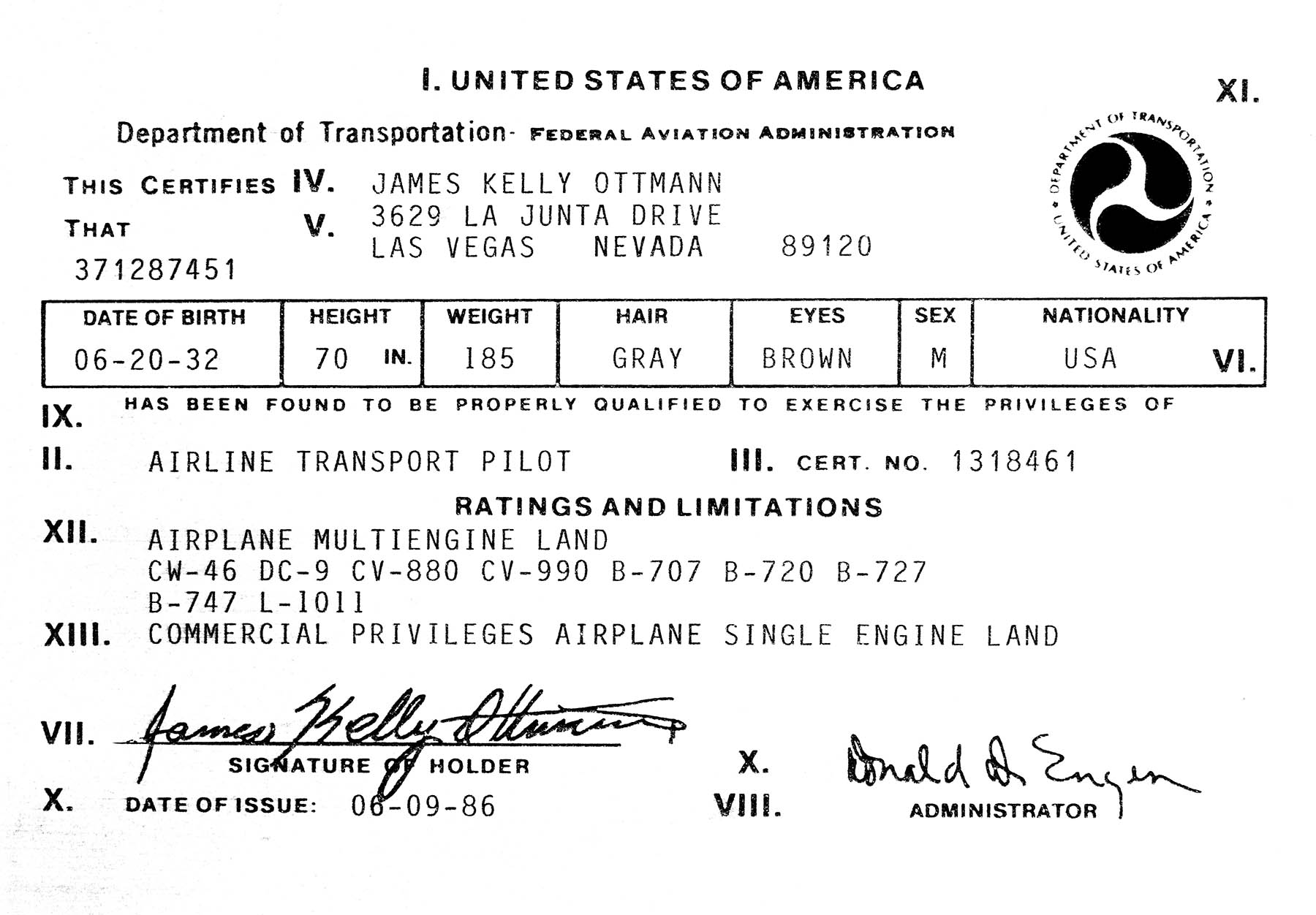

James Ottmann – Airline Pilot

As a young boy, James Kelly Ottmann was mesmerized by the World War II flyboys and their maneuvers over K.I. Sawyer Air Force Base near the center of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He dreamed of joining them someday.

Following a four-year stint in the Air Force as an armorer, Ottmann enrolled at the University of Michigan with a goal of becoming a civil engineer. He married his high school sweetheart, Charlotte Ann Lindbom, and before long, the family grew to four after the birth of daughters, Jan, and Joan.

Ottmann’s unremitted love of flying led him to swap a career in engineering – a plan that represented his father’s dream for him – for pilot’s lessons. He went on to work for Zantop Air Transportation, a Michigan-based freight airline for the auto industry. The job required extensive travel for Ottmann and his family.

Joan Rhoades, Ottmann’s youngest daughter, recalls moving eight times in the early stages of elementary school. The new pilot was making the most of his dream career.

Ottmann answers questions from two FAA agents after he was forced to dump jet fuel in a waterway following a bird strike near Boston.

“He was always moving up the ladder. He was a very bright guy.” said Rhoades, of Clinton.

The demand for pilots during the Vietnam War created a shortage of commercial airline pilots and an opportunity for aviators like Ottmann. With the age for new pilots raised to 32, Ottmann qualified to begin training to fly a commercial aircraft. He went to work for TWA.

A bird strike damaged one of Ottmann’s engines near Boston forcing him to dump fuel for an emergency landing.

The new job with its potential of more travel initially took a toll on the family. Ottmann’s wife stayed behind in Michigan near her family when Ottmann relocated to Chicago for his commercial flight training. But after a brief separation and Ottmann’s purchase of a home in Hoffman Estates, the family reunited.

The week-long trips for his domestic flight schedule left the girls without their father for much of their growing years and their mother to carry the full load of parenting, but Rhoades points out, there were perks to having a TWA pilot for a dad.

“He was a rock star. He blew the other dads away on the ‘Bring a dad to school’ days,” said Rhoades.

Domestic and international travel was also readily accessible to the Ottmanns because of their connection to the airline. First class domestic tickets cost $5 and international fees were $15 per person.

In addition to stateside travel, the family made a three-week tours of TWA hubs worldwide, including Hong Kong, Athens, Bombay, and Tel Aviv. The last leg of the trip from Indianapolis to Chicago was made on a bus after a snowstorm grounded their plane.

After the Ottmann daughters left home for college, the couple moved to Las Vegas, where Ann Ottmann volunteered her training as a nurse to help babies addicted to drugs.

Ottmann’s base with TWA was St. Louis but he shuttled between the airport and his home for work. At 55, health issues forced Ottmann into retirement from TWA and flying. He was an International Captain, flying the L-1011 when he left his post.

In 1995, the Ottmanns moved to Clinton to be close to their daughters and their families. Ann died six months after the move and Ottmann died in 1995.

His affection for aviation never diminished, according to Rhoades. He passed along that passion to Jan, who was ready for a solo flight but did not complete the process because she lacked financial resources for the expensive final portion of licensure.

Recent Comments